|

Getty Villa

Page 2 of 4

http://www.getty.edu/visit/

October 1, 2009

Posted December 22, 2009

© 2009, Herbert E. Lindberg

This page is part of a multi-tour

visit with Walt and Hazel:

|

We continue onto Page 2 with no further

introduction:

|

| Interior courtyard, main entrance on right |

|

| View

across courtyard from main entrance end (statues here are reproductions) |

|

| Another

view, straight down the courtyard pond |

|

| Closer

view of a pair of courtyard statues |

|

Sarcophagus

with Scenes from the Life of Achilles; Roman, made in Attica, Greece, A.D.

180--220, Marble

Even centuries after the Trojan War was fought, its epic

stories remained popular, as exemplified by the Images carved on this

monumental Roman sarcophagus (coffin). It is decorated on three sides with

scenes from the life of Achilles. On the right side (not seen here), Odysseus discovers the

hero hiding among the daughters of Lykomedes on the island of Skyros. On the

left side (also not seen), Achilles dons his armor with Odysseus's help. On the front,

Achilles mounts his chariot to drag Hector's slain and stripped body before

the walls of Troy.

The back of the sarcophagus is shallowly sculpted with an

unrelated scene of battle between the Greeks and the centaurs (part man,

part horse). The lid shows a couple reclining on a couch. The sculptor

deliberately left their heads unfinished so that the owners of the coffin

could have the portraits carved.

|

|

| Elaborate

bowl |

|

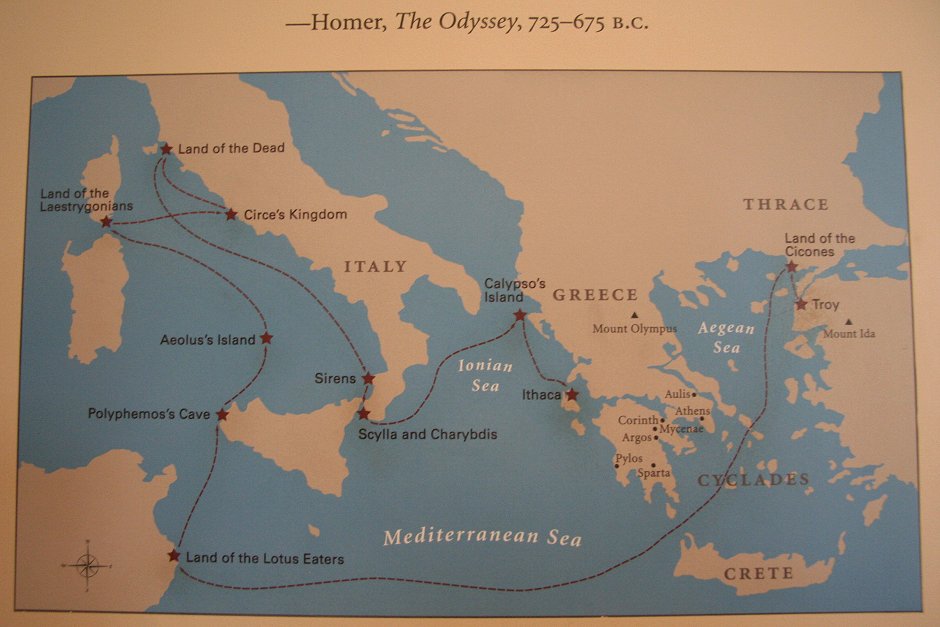

Map

of Odysseus's journey home, to support descriptions of art objects related

to The Odyssey

Homer's epic poem

The Odyssey tells of the Greek hero Odysseus's ten-year journey from

Troy back to Ithaca, his island home. Along the way, he and his crew are

plagued by the gods and encounter numerous monsters and wondrous creatures,

such as the one-eyed Cyclops Polyphemos, the enchantress Circe, the seductive

Sirens, and the monstrous Scylla and Charybdis. After enduring years of

hardship, Odysseus arrives in Ithaca to find his home invaded by suitors

courting his wife, Penelope. She had delayed selecting one of them to be her

husband by promising to wed when she finished weaving a tapestry, which she

secretly unraveled at the end of each day. Odysseus's return leads to the

slaughter of the suitors and a reunion with his wife.

|

|

Poet

as Orpheus with Two Sirens

Greek, made in Taras, South Italy, 350--300 B.C., terracotta and pigment

Orpheus, the son of Apollo (god of prophecy and music) and a

Muse, was considered the most skilled singer in antiquity. He is best known

for his failed attempt to rescue his wife, Eurydike, from the Under-world.

Another adventure is alluded to here: Sailing with Jason and the Argonauts,

Orpheus encountered the Sirens, mythical bird-women whose seductive singing

lured Sailors to their deaths. Orpheus rescued his companions with a song so

beautiful that the Sirens despaired and threw themselves into the sea.

This seated man has been identified as Orpheus because the

statue once

cradled a lyre in its left arm and his mouth seems to be open in song. The

cult of Orpheus, which promoted a belief in life after death, flourished in

southern Italy, where this group was made. In South Italian art of this

period, however, Orpheus usually wears an Eastern costume, which is not seen

on this figure. Since Sirens often appear on tombs, mourning and protecting

the dead, he may be a mortal, perhaps a poet or a singer, depicted as Orpheus

in a funerary monument.

|

|

| Close-up

of Orpheus (Note the many fragments that had to be assembled.) |

|

Hercules; Roman, A.D.

100--200, Marble and pigment

The greatest of the Greek heroes, Herakles was

enthusiastically adopted by the Romans, who called him Hercules. Although this

statue has been damaged over time, the hero's standard symbols—the skin of

the Nemean lion and the club—identify him. Here Hercules also wears a wreath

of white poplar leaves and a fillet (ribbon) with its ends trailing over his

shoulders. The fillet marks him as an athletic victor, and white

poplar was associated with the

Olyrnpic Games, which the hero was credited with founding in honor of his

father, Zeus (king of the gods). According to tradition, Herakles imported

white poplar from northwestern Greece, and it was the only wood used to fuel

the altars at Olyrnpia. Statues such as this one were extremely popular,

commonly appearing in Greek and Roman gymnasiums, where athletes trained.

|

|

Wine Cup with Athena and Herakles Fighting the

Giants; Greek, made in Athens, 540--530 B.C.

Scenes from the Gigantomachy, a mythical battle between

the gods and the giants, adorn this vessel. In the center, Athena

(goddess of warfare) prepares for battle. Her opponents emerge

menacingly from behind the eyebrows of the two large eyes. Near one

handle, the hero Herakles (identified by his lionskin) fights a giant. A

prophecy had foretold that the gods could not win without the help of a

mortal, so Herakles came to the aid of the gods at Athena's demand.

|

|

Appliqué

of a Boy Wearing a Lionskin; Greek, about 100 B.C., Bronze

Although this appliqué

seems to depict a young Herakles wearing his lionskin, it more likely

represents another figure with the hero's attribute. The delicate features and

the distinctive topknot suggest that this is Eros (child god of love), who was

often shown with the symbols of other mythological figures. A quiver strap

crosses his chest, and remnants of wings survive at his shoulders.

|

|

The

Lansdowne Herakles

This

sculpture was one of J. Paul Getty's most prized possessions and, in fact,

inspired him to build this Museum in the style of an ancient Roman villa.

The statue, representing the Greek hero Herakles with his lionskin and club,

was discovered in 1790 near the villa of the Roman emperor Hadrian (ruled

A.D. 117--138) at Tivoli, Italy. It was purchased in 1792 by an English

collector, the Marques of Lansdowne, to become part of his extensive private

collection of ancient sculptures.

Shortly

after its discovery, the statue was reworked in Rome, probably by Carlo

Albacini, a prominent restorer. A spirit of purism caused it to be stripped

of its restorations in the 1970s, but these historical additions were

reintegrated in the 1990s to present the work as it appeared in the

eighteenth century.

|

|

Satyr

Pouring Wine; Roman, A.D. 1-100, Marble

Modeled after a popular work by the famed Greek sculptor

Praxiteles (active about 375-340 B.C.) this statue represents a young satyr

pouring wine from a now-missing pitcher into a cup once held in his left

hand. Satyrs were part-human, part-horse or -goat companions of Dionysos

(god of wine). Only the pointed, animal like ear of this figure identify him

as a satyr.

The sculpture was one of four identical figures that

decorated the villa of the emperor Domitian (ruled A.D. 81-96) near Castel

Gandolfo, Italy. This one was missing its head when it was discovered in

1657. By copying the head of another of the satyr statues, the work was

restored in the seventeenth century.

|

|

| Gallery

with four muse statues between the columns. |

|

Continue to Page 3 | Return to

Page 1 | Home

|