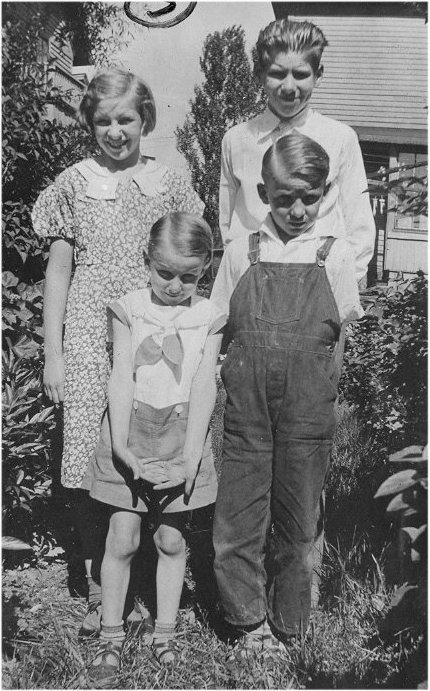

(taken in Grandma's back yard at the time of the story)

|

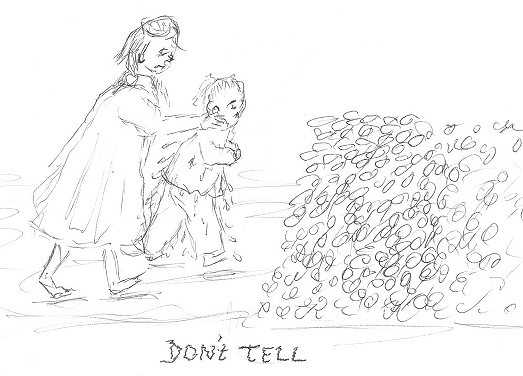

After the male contingent left, Bert and I asked if we could go out to play in the garden. Ma and Grandma hesitated because the garden was bordered across the back and along one side by the lake located behind our Grandparent's home. The lake was about three feet deep where the garden edges dropped sharply into it, and only a hedge fenced those edges. It wasn't the safest place for young children to play. At the corner where the two hedges met Grandpa had made an opening and built a little wooden pier about two feet wide and three feet long. There were fish in the lake and he actually fished from there. Bert loved to take a stick and pretend it was a fishing rod. He would stand close to the end of the pier, stretch out his arm to hold the stick as far over the water as he could, and hope that he might really catch a fish. The family never left him alone there. I was ten that summer and had been helping Ma look after Bert since he was six months old. She and Pa took for granted that I was mature enough by then to take full responsibility for his safety. We were allowed to go. It was a morning cold enough to see our breaths. I put on a warm outer garment and Ma dressed Bert in his old almost outgrown, winter, heavily lined, gray tweed suit coat. Before we went out we were given a warning to stay away from the water and especially the little pier. Ma and Grandma explained why we could easily drown if we fell into the lake. Its bottom was a thick muck that would suck us down and we were not yet big and strong enough to escape from it. The lecture over, we scooted outside. Happily released into the bright outdoors, we headed down the path to the back of the garden where we could look through the hedge and see the lake. We were city kids who knew almost nothing but brick, cement and city stink. Being away from that, surrounded by Grandma's abundant flowers and with a real lake at our feet, we were in a Never Never Land. Of course Bert headed straight for the pier and his fishing stick. I tried to talk him away from it but he was a stubborn little guy and wouldn't give up his game. He kept at it while I could only stand at the foot of the pier to watch over him. My memory is blank here. I don't know how long we were there or what made me turn away from him but I do remember hearing a quiet splash behind me. Even before I turned back to him I knew he had fallen into the lake. The sight I saw terrified me. Only his ankles and feet were sticking out of the water with the soles of his shoes flat to the sky. They were already sinking slowly, telling me that the muck at the lake bottom was pulling him down. |

|

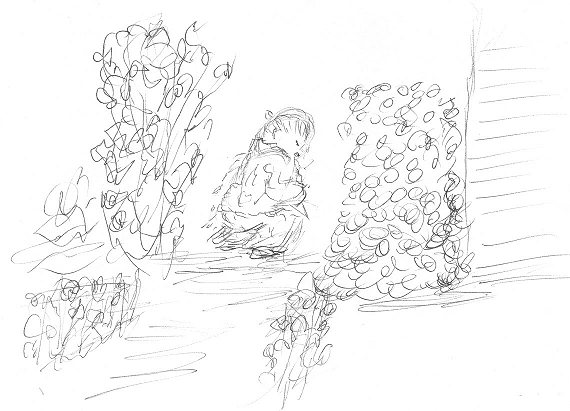

My instinct told me run and fetch Ma and Grandma but our human minds are full of surprises. My ten year old mind suddenly switched from instinct to a mode of skilled logic. "I can't go for them.", I thought, "If I do he will be completely gone by the time we come back. I have to do something now." I couldn't think of a way to grab his feet. They were too far from the pier for me to reach and I didn't know how to swim. At my young age, I was already five feet tall so the water wasn't too deep for me but how deep was the muck at the bottom? If I jumped into the water with my heavy clothes on I could sink into the muck too and we would both drown. I felt totally helpless looking at those sinking feet while trying to think of a way to grab them. Suddenly they disappeared completely. My stomach tightened with fear but almost immediately his head popped up to where his feet had been. His face was gray from cold. His blue eyes, wide open with fear, were looking straight into mine begging for help. His mouth was also wide open in a silent scream that was much more frightening to me than if he had been shrieking. |

I have learned since then why his scream was silent. The lake water was ice cold. When a person is suddenly submerged into ice cold water their muscles seize up, making breathing almost impossible. Bert couldn't breathe so he couldn't scream. He was sinking again and his lower lip was already under the water.

Being right side up, at least his hands were free to grab if only I could find something for him to grab. His stick was lying on the pier so I held it out to him. It was much too short and I could see it was too flimsy to hold him. There had to be something else I could use. Maybe I could tear a limb from one of the bushes but any that I could pull off wouldn't be strong enough to hold him. I was terrified but that strange logic kept me from panicking. I searched the ground for a possible fallen sturdy branch but found nothing. Grandma kept an immaculate garden.

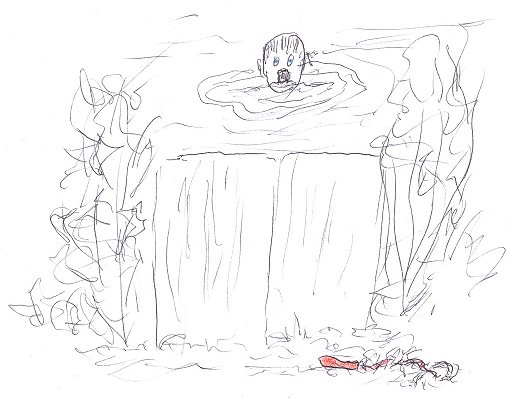

Bert kept sinking. The water was almost to the upper lip of his open, silently screaming mouth. His big frightened blue eyes were still begging me for help. There had to be a way for me to save him before he was sucked under the water and gone. I searched the ground again and there, almost at my feet and partially covered by a few fallen leaves, lay a jump rope. It was the red paint of its handle showing through the leaves that caught my eye. I picked it up and found it was only half there but it would have to do.

Jump ropes were made much more sturdily in those days than they are now. The ropes were thicker with solid wooden handles turned to fit the grasp of a human hand. I knew the handle would float, and the rope that was left looked long enough to reach Bert's outstretched hands. If I could just get that handle to him I might be able to pull him out of the water.

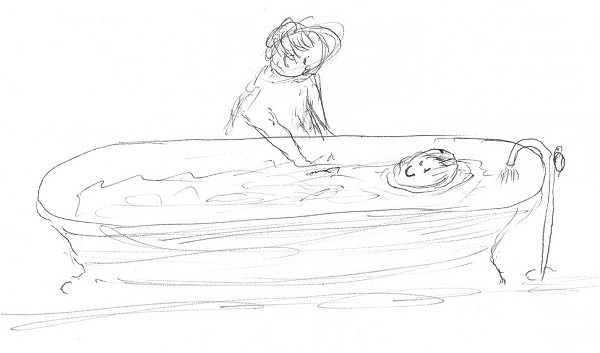

Did I lie on my stomach or did I kneel while I was on that little pier throwing the jump rope to Bert? I don't remember. I do remember that it took only one or two throws to land that red handle where he could grab it. When he did he locked both of his hands around it in the frozen grip of a drowning person, which is just what he was. My hands were holding onto the other end of the rope with the same kind of grip. He hung on and I pulled with all my might. I saw the rope become absolutely taught as he inched out of the water. I can remember hoping it wouldn't break because it was such an old rope.

It held. We were not only lifting Bert but the weight of his clothes. That warm tweed coat Ma had dressed him in acted like a sponge and was swollen to twice its dry thickness. Bert could barely bend his arms. Again, I can't remember every detail but I do remember the immense relief when, with me pulling and Bert clawing, we finally dragged his torso over the end of the pier. After that we let go of the rope and between us we wiggled Bert the rest of the way onto the pier.

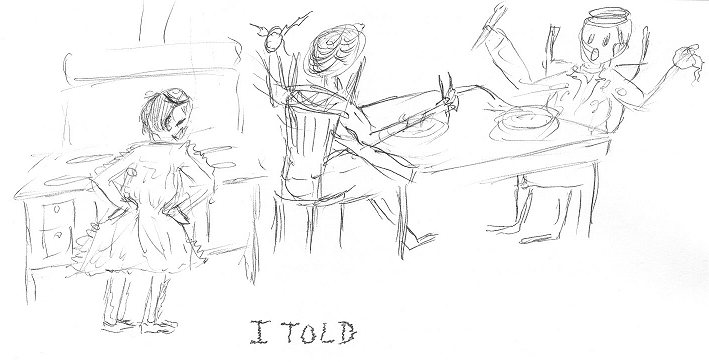

The rest of this tale belongs in a comic book. My mind reverted to a scared witless ten years old.